The recent poor performances of Nigeria at global youth soccer competitions is a dire warning about the future. These are competitions where Nigeria had been traditionally strong not just in the continent but also globally.

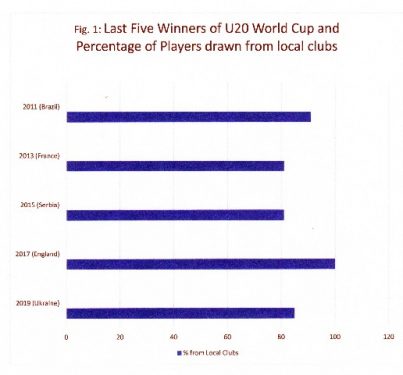

However, while one could claim that recent results may be aberrations there is a certain tendency that is undeniable. It is a tendency towards using significant number of foreign-based footballers in Nigeria’s national youth teams. That tendency, discussed below, moves in the direction that counters what recent championship winning teams are doing at the global level (see Figure 1).

There is nothing inherently wrong in selecting foreign-based players for the national youth teams if the competitive environment favours it. After all, such players are Nigerian citizens and moving to a foreign land or being born in a foreign country should not deny them opportunity to represent Nigeria. The issue, however, is whether foreign-residency adversely impacts Nigeria’s youth national team and if it does, how?

The data that are available, although not exhaustive, indicate that significantly selecting members of the youth national team from players resident abroad may be a hindrance to high level performance if measured by results. What is not known is exactly why.

There may be an explanation such as the role of FIFA’s current statutes. FIFA statutes adversely affect teams that select a significant number of players from players resident abroad. FIFA’s enforceable release of players to national teams covers only invitations for games scheduled during International Match Weeks, which are often dedicated to games involving the senior and not youth national teams.

A national FA can get around this rule if players are selected within its country because it can arrange regular midweek camps for youth players and request the local clubs to release invited players. Unfortunately, this is not feasible when a player is resident abroad and away from the control of his/her national FA.

Increasingly, and particularly under the current NFF regime, Nigeria has boldly tied its performance to the use of footballers residing overseas. The effect has been dramatic at youth levels as is shown in the 2019 U20 team to the World Cup.

The U20 team is selected here as example based on the fact that we can compare the teams across several years because the use of a player’s self-declaration of age in player invitation has been stable over the years. The U17 cannot be used as an example based on the change of the age determination method across the years, which makes it difficult to compare teams.

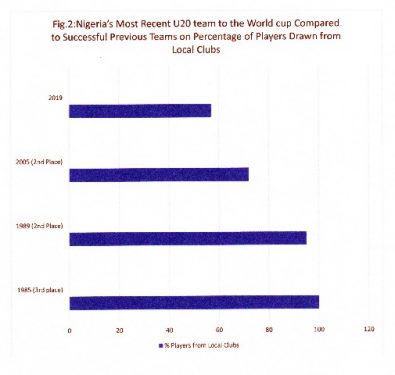

Here, team composition (selection of local v foreign-based players) is explored. The U20 data show a major change in team composition comparing the successful years of 1985, 1989, and 2005 to the 2019 team (see Figure 2).

Successful year is calculated as finishing in the medal round of the FIFA U20 World Cup. Note that although the 2005 team shows that just 72% of the players were drawn from local clubs, it is important to add that the foreign-based players on that team (Mikel Obi, Chinedu Obasi, Solomon Okoronkwo, Taye Taiwo, and Olubayo Adefemi) had already played together with the locally-based players at a younger age group.

This togetherness or familiarity is critical in team sports. Figure 2 demonstrates that while the successful teams were dominated by choice of locally based talents, the 2019 was not. Although, one can also argue that unsuccessful U20 teams were also locally-based until recently.

Examining the 2019 team, with several members playing for European clubs, it is easy to assume that they are better than previous U20 teams but that assumption has not been affirmed by success on the field. Nevertheless, that assumption is based on the Nigerian belief that a foreign-based talent has received “football education,” which his/her counterpart in Nigeria lacks.

The Issue of “Football Education”

“Football Education” is one of the most misused words in discussing football in Nigeria. Unfortunately, those words have suddenly become the alpha and omega of football discussions. First, there is no talented footballer that is not football educated. You are either educated formally or informally.

Second, there is no one type of football education. It varies depending on type of football that is to be played. A footballer that is informally educated in the streets is not a lost case. He or she simply becomes challenged to be educated in a different way and formally when he seeks to play professionally. He either adjusts or fails to adjust.

This is why the so-called uneducated Nigerian footballer can make the squad of an elite club in Europe ahead of several European players who had been receiving the so-called football education for years. This also explains why a Nigerian player, educated differently, may find it difficult to adjust to a different education at an elite European club. It also explains why a “football educated” European player may fail to adjust at another elite European club requiring a different type of football education.

Nonetheless, with the tendency to use an increasing number of foreign based Nigerian players, one expects the “football education” acquired in Europe to become prominent. Yet, the recent results have not affirmed this especially when compared to the period the country used the so-called uneducated or poorly “football educated” players.

The Coaching

If those supposedly “football educated” fail, who is there to blame? Perhaps, the coach. However, the recent Nigerian U20 coach at the World Cup held the highly regarded UEFA Pro certificate. It is a much higher certificate than Nigerian coaches, who have done well at the same tournament, ever held. So what gives?

The Issue of Team Chemistry

Perhaps, it is the issue of team chemistry that should matter. It requires not just quality coaching but time. Relying on foreign-based players, who may not be released or are released very late by their foreign clubs, is to ignore the importance of team chemistry i.e. building a team familiarity that reaches the level of seamlessness and effectiveness.

Instead, that reliance on a large number of foreign-based talent, coupled with unsupportive FIFA scheduling, puts Nigeria at a disadvantage. A team does not necessarily need 11 best players pound for pound. An effective team may well be slightly less talented but by each player understanding fully his role viz a viz other players, the team’s sum of its parts will always outweigh the sum from 11 most talented players that lack team familiarity.

This is particularly critical at youth level where the tenure of a team is short-lived. At the senior level, chemistry is developed because of the use of a core group of players over a long period, a period unlikely to be available to youth teams except when the team is selected from one or few clubs, selected largely from local clubs, or are transitioned en masse from one age group to the next.

Conclusion

Ultimately, Nigeria should consider recent results as dire warning for the future and it is time to re-think the current direction. While the goal may not always be to win youth tournaments, it remains important to do well in such competitions if only as a measure of progress in youth development.

Nigeria is not the only country that has multiple talents abroad. In fact, countries like Brazil and Argentina have far younger talents abroad but yet those countries largely consider FIFA edicts and the issue of team chemistry in focusing youth developments inwards.