A train-wreck. An unmitigated disaster. A catastrophe. Call it what you will, there’s no question that Liverpool’s defense of its first title in 30 years as gone spectacularly off the rails. Last Sunday’s home defeat to Fulham marked an unprecedented sixth consecutive home defeat in the Premier League.

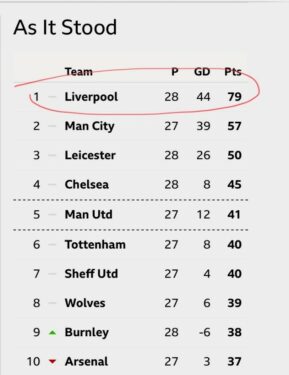

The contrast to last season, when Liverpool set all sorts of records couldn’t be any starker: at week 28 a little over a year ago, the Reds boasted a scarcely believable record of 26 wins and one draw. They had just matched Man City’s PL record of 18 consecutive wins (ended at Watford that match week) and would eventually finish well clear of second with 99 points.

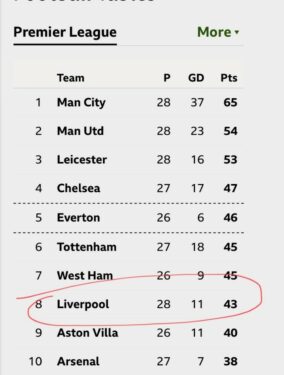

Here’s an even better contrast: Man City are currently enjoying a remarkably consistent run that has them sat on 65 points from 28 games and a comfortable 11 point lead at the top of the table, an excellent season that will see them crowned champions; Liverpool, at the same point a year ago, had 79 points and a 22 point lead!

2019/20 2020/21

The root cause of Liverpool’s capitulation is no mystery of course. Such has been the injury crisis that has ravaged Jirgen Klopp’s squad – especially in central defence – that it’s a wonder they still managed to muster a title defense of sorts until Christmas before things started to fall apart.

There is certainly much more to it than the flippant “they are missing Virgil Van Dijk” conclusion that has been drawn in many quarters. It all started with Van Dijk of course. His season ended with a torn ACL at Goodison in week 5 and his absence continues to be a big factor in Liverpool’s woes this season.

Take the best centre back in the world out of any team and there’s bound to be a negative effect.

But Liverpool’s troubles go well beyond the absence of Van Dijk. Since the big Dutchman took his leave, he has subsequently been joined on the sidelines – with season ending injuries – by fellow centre backs Joe Gomez and Joel Matip. In their absence, much of the burden had been carried by Fabinho, normally a defensive midfielder, but he’s now missed the last six Premier League games (he returned for a second half appearance against Fulham at the weekend).

Captain Jordan Henderson, who had also been filling in at centre back, has now joined the wounded ranks too, and won’t be back for a long while. It’s one thing to be forced to juggle and constantly rotate four senior centre backs; it’s quite another to have to sift through central midfielders, inexperienced fifth and sixth choice options and a couple of brand-new arrivals. Liverpool’s 20 central defensive pairings in 28 matches is the very definition of instability.

Take all the centre backs (and their midfield stand-ins) out of any team and there’s bound to be a negative effect.

And it’s not just defending that has suffered. In truth, the team actually coped admirably defensively until a recent spate of errors that saw them ship nine goals in three games. But without the composure and passing range that Van Dijk especially brings to this team, the build up play has suffered as well.

Then there’s the knock-on effect of pulling both Henderson and Fabinho out of midfield – both are nailed on starters, both have been nailed on, first choice starters for two seasons – and it’s easy to see why Liverpool have been far from their dominant, energetic high-pressing best.

The attack hasn’t been without its troubles too – even if the only notable injury absence has been that of new boy Diogo Jota, who has just returned from a three-month hiatus. It’s not abnormal that the lack of stability elsewhere in the team would trickle down into attacking areas, but it’s also true that the usually reliable trio of Mo Salah, Bobby Firmino and Sadio Mane have chosen the worst possible time to suffer an alarming dip in form.

The list of Liverpool results from Boxing Day to January 30th reads like a binary code sequence and tells the story perfectly: 1-1, 0-0, 0-1, 0-0, 0-1. That’s not indicative of defensive problems. Liverpool have now gone almost 8 full games at Anfield without scoring a goal from open play (they’ve scored just once, a penalty) since Mane’s 10th minute goal against WBA on Boxing Day. We are in March.

Whatever the diagnosis, what is clear is that Liverpool has been unable to bring to bear the two key factors that made them successful in what remains one of the toughest leagues in world football.

The first of these is chemistry – team chemistry. As I noted in my Liverpool season preview at the start of the 2019/20 season, it’s the one key factor that Klopp was counting on for success, even as fans and pundits decried the lack of new signings.

“It’s that familiarity, that collective development – that chemistry – that took this team to great heights last season, and it’s what Klopp will be betting on again this season.

They will be contenders again.”

It worked a treat too. When Jordan Henderson lifted the Premier League trophy on the Kop what seemed an eternity later, it was the crowning glory of a season that brought out the very benefits of Klopp’s belief in collective growth and continuity.

It was chemistry built on the consistency and endurance of Van Dijk alongside no more than three partners in central defense; chemistry based on the familiarity and unison of Fabinho, Henderson and Gini Wijnaldum in midfield; chemistry based on the fluid, interchangeable rhythm of Firmino, Mane and Salah in attack.

Chemistry forged on the fact that Liverpool’s first choice XI at the end of 2019/20 still included eight of the team that started the 2018 Champions League final in Kiev – the odd ones out being Gomez (who was in the 2018 squad), and the Brazilians Alisson and Fabinho (who had already been at the club for two years).

Champions League Final 2018

Liverpool

Starting XI: Karius; Alexander-Arnold, Lovren, Van Dijk, Robertson; Henderson, Milner, Wijnaldum; Salah, Mane, Firmino.

Contrast that to this season and what an unprecedented injury crisis as wreaked on this Liverpool team. In the last two months we’ve seen a fragile team led by the same injury-free but out of tune front three, now backed up by what is essentially a brand-new midfield comprising a trio of players still getting to know one another, and a defence back-stopped by a revolving cast of centre backs. Certainly, 20 different centre back partnerships is not a recipe for continuity and chemistry; it’s a recipe for disaster.

The second key factor is versatility. One of the key strengths of this Liverpool team over the past two seasons is the variety of ways in which they could hurt opponents. Klopp’s beloved counter-press has always been his team’s prime calling card, their relentless high press setting traps, forcing errors and creating chances for the front three to exploit.

When that has not worked, they could turn to the wings, where Alexander-Arnold and Robertson have forged a reputation as the most creative full back pairing in all of Europe (49 assists in 18/19 and 19/20). Then there is the deadly counter attacking game that has so often punished opponents – often from their own corner kicks, or from quick switches of play.

Above all that though, there’s Liverpool’s prowess at set pieces, an asset that has proved one of their major tools over the last two seasons. Heck, they’ve even scored from set pieces in each of their two Champions League finals.

All that made for a team well equipped to cope with all manner of problems: if you played out from the back, the high press would get you; if you defended deep and narrow, the full backs would find a way; if you pushed up too high, Mane and Salah would do you with their pace; if you played it high and long, Van Dijk and Matip were imperious in the air; if you looked to exploit the spaces behind their high line, Van Dijk and Gomez had the pace and defensive nous to match the speediest opponents.

You get the picture – on their day, which was often, this team was damned hard to beat.

That is the level of versatility – that variety, that unpredictability – that has been taken out of this team this season. It’s not just a case of missing defenders or midfielders; it’s the impact of their loss on the team’s ability to function with the full toolkit that’s brought it great success for three years.

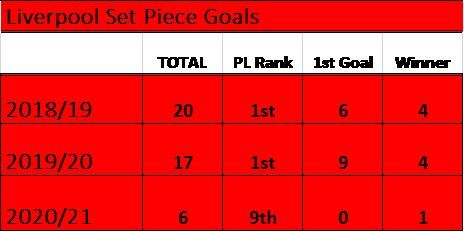

The set piece numbers illustrate this very clearly. Take those assist numbers for one thing: Liverpool’s full backs have contributed a combined total of 10 assists this season (up to week 28). For a pair that has averaged 25 over the last two seasons, many from free kicks and corner kicks, that’s a steep drop off, that naturally mirrors the drop off in Liverpool goals from free kicks and corner kicks.

Liverpool led the Premier League in set piece goals last season (17, jointly with Man City)- as they also did in 2018/19 (20). This season, with 10 games remaining, they’ve managed 6 goals from set pieces. That ranks them 9th in the Premier League. The set piece kings have become set piece…nothings.

That is an obvious consequence of losing the height and aerial prowess of two of the most aerially dominant centre backs in the Premier League. It’s no coincidence that four of Liverpool’s set piece goals this season involved Van Dijk and Matip.

Van Dijk has missed 24 games; Matip has missed 18. The Dutchman is particularly deadly from set pieces – 12 of his 13 Liverpool goals have come directly from set pieces and he has scored more PL goals than any defender over the last two seasons. The mere presence of those two (6 ft 4 in and 6 ft 5 in respectively) at set pieces brings not only an extra threat, but also extra scrutiny which draws attention away from others (like Mane and Firmino) making them more of a threat also.

In their absence, Liverpool are a much shorter, less aerially adept team and hence far less of a threat from set pieces.

But beyond the sheer numbers, a deeper dig shows why set piece goals have been so important to Liverpool’s recent success. Of last season’s 17 set piece goals, no less than 13 were either opening goals or winning goals. In 2018/19, that number was 10 of 20 set piece goals.

A good example is the home game against Brighton last season when two Van Dijk headers – from Alexander-Arnold deliveries – made the difference in a 2-1 win. Van Dijk’s towering header also provided the early breakthrough in the January defeat of Man Utd at Anfield, and who could forget Mane’s dramatic late winner at Villa Park in October? In contrast, that has only happened once this season – Firmino’s late winner against Spurs in December.

Now, questions are being asked about the team’s mentality – that never-say-die, unrelenting will to win – that seemed to drive them from strength-to-strength over the last two seasons. But what is mentality without ability? I mean, these players didn’t suddenly lose their mentality over the last few months; what they’ve lost is the ability – the ability to perform at the peak of their powers, the ability to bring to bear the key factors that made them so successful over the last two seasons.

Chemistry, versatility…and set pieces.